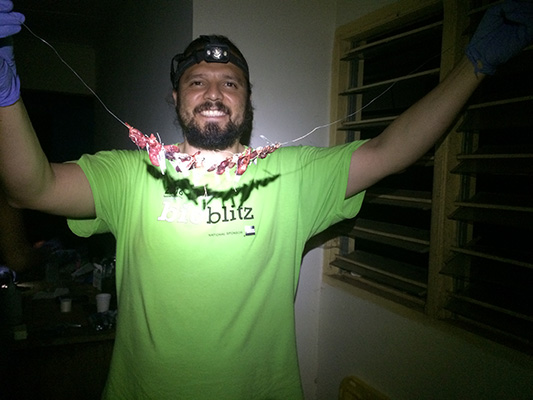

In our series, "Scientist in the Spotlight" we’ll sit down with the ADBC (Advancing Digitization of Biodiversity Collections) program's best and brightest to learn more about what makes them tick. This month, we had a chance to speak with Noé De La Sancha. He is a part of the oVert TCN.

Where are you from?

I was born in Toluca, Mexico. When I was four years old, my family and I immigrated to the United States. Eventually, we moved to Sunland Park in Southern New Mexico. In many ways that is my home, the Chihuahua desert.

When did you know you wanted to work in science or be a scientist?

I’ve always liked animals, especially mammals. Since I was a kid, I swore I was going to be a veterinarian. To be honest I never knew what being a scientist was. I never met any scientists growing up. In high school, I had an awesome environmental science teacher. He took us to pick up trash on the weekends, to picket the local landfill, and to lobby the State Senate in Santa Fe, New Mexico. When I went to college in northern Wisconsin, I started with the idea of “pre-vet.” I needed a major to be on that track, so I ended up with a double major in biology and environmental science. Then, I had the opportunity to volunteer at a veterinary clinic for several months and I realized that was not for me.

During my time in undergrad, I was lucky to travel several times abroad. One of these was a trip to Botswana in southern Africa. This was part of a class called Global Ecology, where we got to be on safari for close to a month in Chobe National Park. I then got to take a Tropical Ecology course in Costa Rica where we learned a great deal about deforestation of tropical forests. That's when it all came together for me, my interest in animals (mammals), environmental science, ecology, and field biology.

How would you describe your job to a child?

I'm a mammalogist. A mammalogist is someone who studies mammals. A mammal is any animal that has fur and hair.

What do you like most about your job?

What do you like most about your job? The thing that I enjoy the most is being able to study and add to the understanding of mammals. Mammals are a way to study the impacts humans are having on our environment worldwide (like deforestation).

There has been at least five major mass extinctions on our planet, in the last 4.5 billion years. The last one was when a massive asteroid hit, what is now the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico, and wiped all large dinosaurs off the planet. We are currently in the sixth mass extinction: the Anthropocene. The main culprit, the new “asteroids,” are humans. We are the ones who are driving the massive extinction of species that are the descendants of billions of years of evolution. We're wiping everything out. The most important aspect of the type of research we do, is that we (as scientists) could potentially have an impact on understanding how humans are affecting biodiversity. We can work to understand the patterns. Hopefully down the road we can develop strategies to minimize that loss of biodiversity.

In my classes I get to talk to my students (~ 80% African Americans and 10% Latino) about the impact we are having on our planet and the species on it, including humans. The coolest thing is when you can explain and tie together concepts like climate change, deforestation, and biodiversity loss, with social inequality and you can see the light bulb moment in the middle of class. It is very satisfying when people, who may never study ecology or mammals leave your class appreciating those subjects. Informing people about the state of the planet is amazing when they get it, but sometimes it's a little depressing at the same time.

Describe a challenge that you’ve faced in your research?

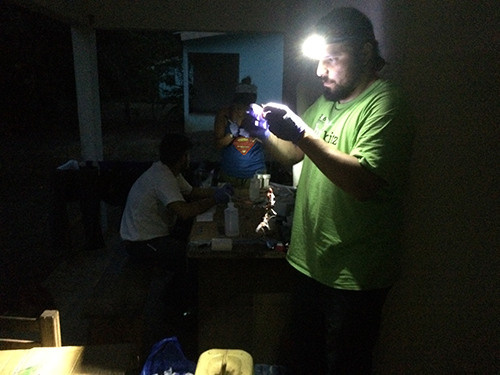

A lot of my PhD work was in eastern Paraguay. We were trying to assess the impacts of deforestation. One of the problems - especially in tropical regions - is that we still don't know how many species we have. For many species, especially small mammals like mice, which are one of the groups that I work with the most, we can't tell them apart in the field. This is a constant struggle with other small mammals like bats, shrews, neotropical marsupials. We just can't distinguish among many of the species in tropical regions, and therefore, that was one of the first challenges that I encountered.

In order to distinguish among species, I had to subsequently learn about many other disciplines, such as taxonomy, phylogenetics, morphometrics, and museum science which I had not immediately associated with ecology. In many ways and more importantly, I learned about the importance of museum collections and voucher specimens. Even after 10 to 15 years of working on these species, we're barely starting to get an idea of the species that are found in what abundances. Since then we've been able to add multiple new genera, species, and records to Paraguay. I think that tells us a lot about our understanding, especially of small mammals.

What do you mean?

We have to be able to tell these things apart if we are going to study biodiversity. Right now, we can't in many parts of the tropics. So, if we think about this, that is a problem for understanding the impacts of deforestation, climate change, and zoonotic diseases.

For example, this is a problem we are currently having with coronavirus. Currently we believe that the coronavirus originated in bats. In a recent study of the origin of coronaviruses, scientists were not able to identify the bats to species and only named the vector as a "horseshoe bat". The problem is that we don’t know how many horseshoe bats we have, which is especially important as we strive to understand the origin of this pandemic.

This is a perfect example of why museum collections are so important, especially for the study of ecology. Rodents are vectors for many potential zoonotic diseases caused by a pathogen that jumps from an animal to a human. If we can’t identify the most basic unit, which is the species of the vector, then any modeling we come up with down the road could be fundamentally flawed. Any inference that we try to make about biodiversity, zoonotic diseases, and climate change would just be stories without the species identification.

What's one interesting fact about yourself that your coworkers do not know?

I think an interesting fact most of my colleagues don’t know is that after undergrad I ended up teaching science in a small elementary school in central Kenya. I got to teach students from 2nd-8th grade for about five months. While I was in Kenya, I got to summit Mt. Kenya, to the highest point one can summit without the use of climbing gear.

What advice would you give to someone younger?

I think that it’s important to realize that one closed door will make you look for other doors you had not considered. After finishing my undergrad career, I was trying to figure out what to do. I ended up traveling and bartending for a few years. At one point I got invited to do training to be an observer on commercial fishing boats in Alaska. I went for a few weeks training in Seattle. I missed getting certified by just a few points!! That was devastating at that moment.

I think that it’s important to realize that one closed door will make you look for other doors you had not considered. After finishing my undergrad career, I was trying to figure out what to do. I ended up traveling and bartending for a few years. At one point I got invited to do training to be an observer on commercial fishing boats in Alaska. I went for a few weeks training in Seattle. I missed getting certified by just a few points!! That was devastating at that moment.

That really hit me hard. After that, I ended up taking a bus to northern Wisconsin, where I was bartending and that ended up being my main drive to apply to graduate school.

Later on, while I was a PhD student, I kept applying for grants to do my field work. One of those funding sources was a Fulbright Scholarship. I had been working on that application for months. About a week before it was due, I went to talk to the Fulbright advisor on campus. She stood outside her door and she said let’s go outside there is a bee in my office. She then informed me that the process was more complex, and I should have talked to her months before and there was no way I could apply that year. While she was telling me this, I asked her about the bee and she pointed to it on the celling. I grabbed a tissue, walked over, got on her desk and grabbed the bee. Then I walked out and let it go. She was so impressed, she said that was amazing, thank you! She said let’s get you a Fulbright! And she sat with me, and we started a year-long process to apply for the following year. The next year I got the Fulbright!

My PhD committee was advising me to shift my plans. However, when I got the Fullbright, that led me to complete my field work in Paragua which led to me attending a Fulbright conference where I met my wife, and subsequently led me to heading to Boston to follow her. I got a Post Doc at University of Rhode Island.

Then we moved to Chicago where she was originally from, which has led me to my current position at Chicago State and affiliation with The Field Museum in Chicago. So the point is you never know what a bad situation today will lead to down the road if you stay positive and keep working.