Thoreau still contributes to climate change research

New study uses Henry David Thoreau’s observations of fruiting times

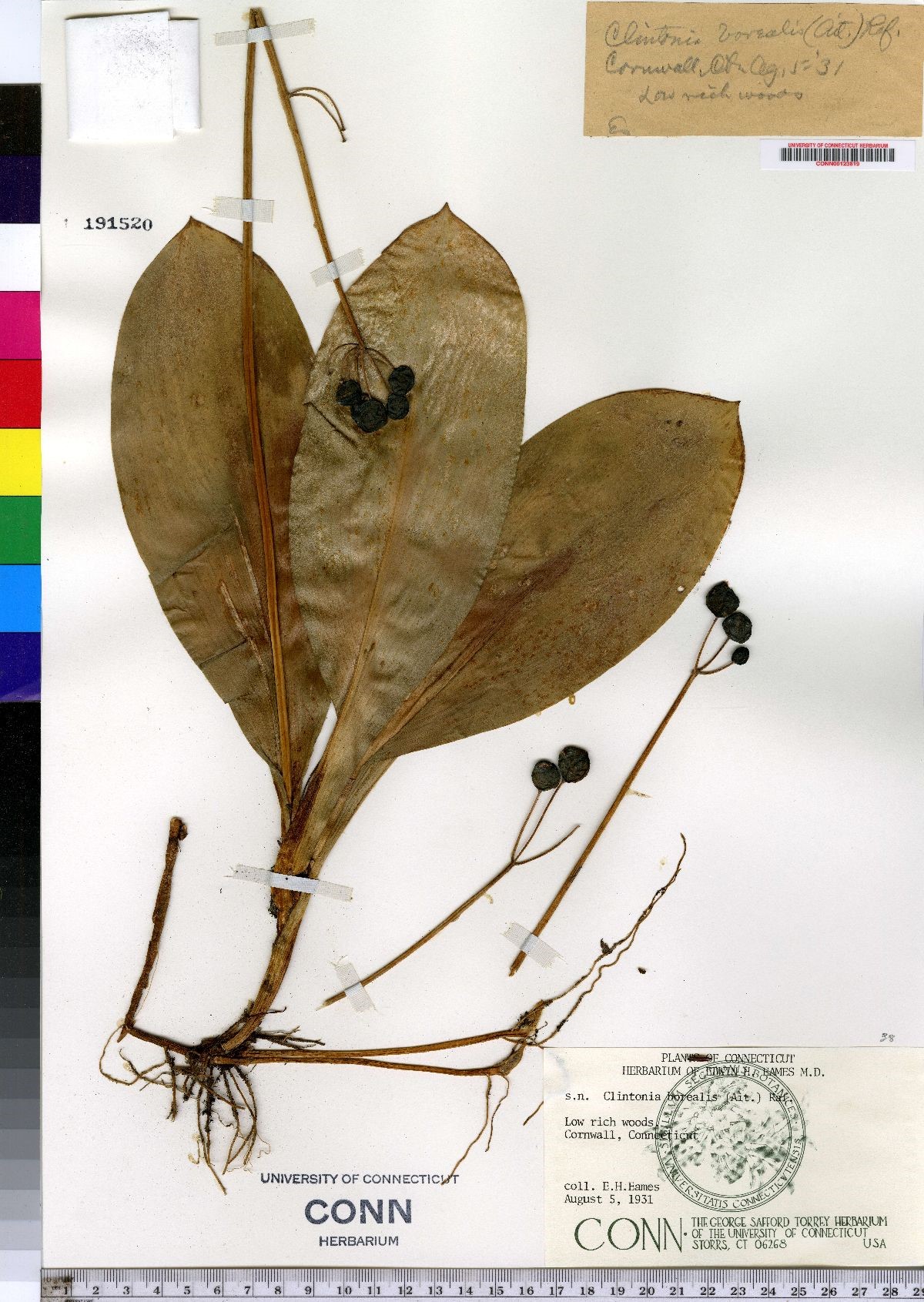

Digitized museum specimens, such this bluebead lily (Clintonia borealis), were used to determine the time of fruit ripening. © Consortium of Northeast Herbaria.

Researchers from Boston University (BU) combined Henry David Thoreau’s fruiting observations from the 1850s in Concord, MA with museum records from the past 150 years across New England to inform research on the biological effects of climate change. In a new article in press in Annals of Botany, BU plant ecologists demonstrate that there is strong sequence of fruiting in New England plants, with species such as blueberries fruiting in mid-summer and hollies fruiting much later in autumn.

This is the first time that Thoreau’s fruiting observations have been used in scientific research, and this work builds on previous studies of Thoreau’s observations of flowering times and bird arrival times. The present study was possible because pressed plant specimens – also known as herbarium specimens – have only recently been digitized in large numbers and made available on-line; these museum observations were then compared to Thoreau’s observations.

Lowbush blueberry plants (Vaccinium angustifolium) were observed to fruit early in the year, based on both Thoreau’s observations and museum specimens. © Jason S. (https://www.flickr.com/photos/arghman/72971352/, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

“It’s exciting that we are able to learn about fruiting plants from Thoreau’s observations made 170 years ago and from museum specimens collected decades ago” says Ph.D. candidate Tara Miller from Boston University, lead author on the study.

The study finds that both Thoreau’s observations and museum specimens detect similar patterns of plant fruiting times, confirming that historical observations and data from museum specimens can be combined to create larger and more powerful data sets for climate change and ecological research. However, the museum specimens are collected over a larger area and over more years than Thoreau’s observations, which were collected over 10 years around Walden Pond and elsewhere in Concord. As a result, the museum observations show an earlier start to fruiting and later ending than Thoreau’s observations. Miller further points out that “Research with herbarium specimens is rapidly expanding, and this is largely due to the effort and funding that have been put into scanning and uploading these specimens online for everyone to see and use.”

This deciduous holly, also known as winterberry (Ilex verticillata), fruits later in the year. © SB Johnny (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ilex_verticillata_fruits_and_foliage_1.JPG, CC BY-SA 3.0).

This deciduous holly, also known as winterberry (Ilex verticillata), fruits later in the year. © SB Johnny (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ilex_verticillata_fruits_and_foliage_1.JPG, CC BY-SA 3.0).

“Our lab group has been working with Thoreau’s observations for 18 years now, and Thoreau still has more to contribute to climate change research” says co-author and principal investigator Prof. Richard Primack from Boston University.

Read the full article: Comparing fruiting phenology across two historical datasets: Thoreau’s observations and herbarium specimens

Authors: Tara K. Miller, Amanda S. Gallinat, Linnea C. Smith, and Richard B. Primack

Questions should be addressed to:

Tara Miller (tkingmil@bu.edu) Corresponding author and Ph.D candidate

Richard Primack (primack@bu.edu) Co-author and Professor