Contributed by: Aaron Goodman, Graduate Student Department of Entomology, California Academy of Sciences.

One of the most ecologically and geologically unique areas on earth is the Baja California Peninsula. Baja California is considered a biodiversity hotspot, possessing high species richness, endemism, and threatened species. The peninsula has undergone a unique geological history, starting with an initial separation from mainland Mexico 4-5 million years ago, followed by subsequent uplift, submergence, fragmentation, and aridification, resulting in the second longest and most isolated peninsula in the world. This complex interplay between geology and environment has had dynamic effects on the evolution and distribution of the landscape’s herpetofauna.

Roughly 161 species of herpetofauna reside within the Peninsula (4 salamanders, 13 frogs, 4 turtles, 84 lizards, 55 snakes, and one amphisbaenian), 48% of which are endemic. The major ecoregions of Baja California possess not only unique plant communities, but each community harbors unique assemblages of herpetofauna. Although checklists and largescale collection expeditions of herpetofauna of Baja California and its Islands have been around since the early 20th century, current species distribution maps are sparse or out of date.

Urbanization, salt-mining, cattle grazing, and hunting are the primary threats to Baja’s pristine environments, and encroachment of these anthropogenic effects have cascading effects on the stability of its various ecoregions. Long-term datasets are necessary to understand population shifts of endemic species in the face of a changing climate. Luckily, there has been a rapid increase in online digitization efforts of museum collections, and even larger aggregations of multi-museum collection databases. We are able to add records in real time, providing a comprehensive and detailed map of species distributions throughout space and time, allowing us to make better informed decisions of areas in need of protection throughout Baja California.

In our recent paper “New record and range expansion of Masticophis lateralis (Hallowell, 1853)(Squamata, Colubridae) into western Baja California Sur, Mexico (DOI:10.15560/15.2.345)" we utilize the iDigBio database to expand the range of the California Striped Racer into a novel ecotype within Baja California Sur.

The California Striped Racer, Masticophis lateralis, is a common fast-moving, medium-sized diurnal species of snake, whose distribution ranges from Northern California, to northwestern Baja. Although specimens have been found in in Northern Baja, and Cabo San Lucas, no records have been documented between these two localities. This paper fills the distributional gap of this species, which now encompasses all of the Baja California Peninsula.

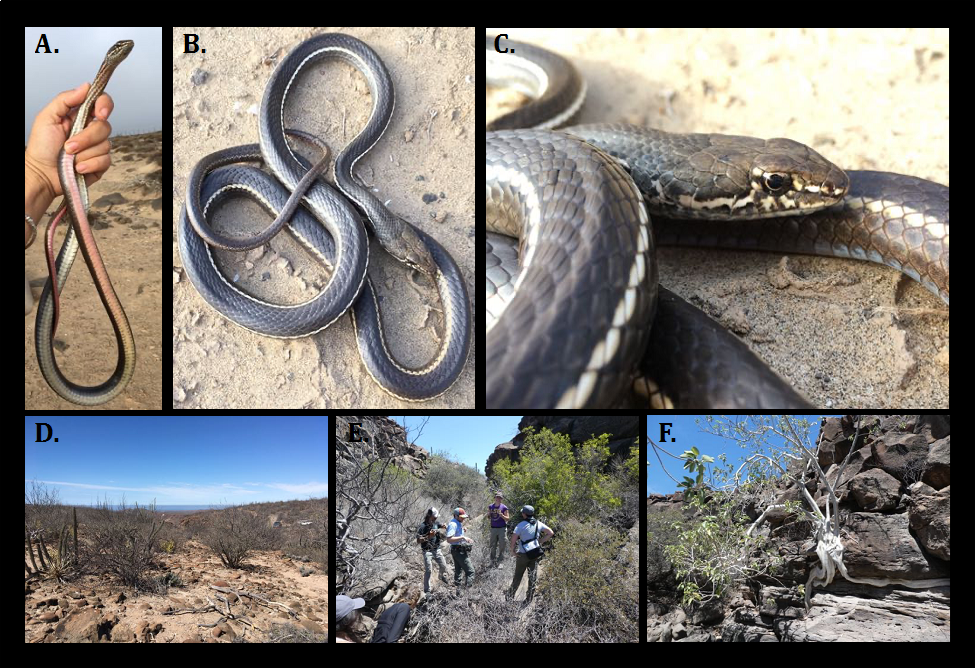

We came across an individual of M. lateralis in the foothills east of San Juanico Bay, Baja California Sur, during a 10-day long field course hosted by the Islands and Seas Field Station (https://www.islandsseas.org/, @islandsseas). The individual was climbing through the branches of a snakewood tree (Colubrina viridis, M.E.Jones, M.C.Johnst. family Rhamnaceae), within a ravine perpendicular to a cliff face. The specimen was not collected because there was no collection permit. However, the external anatomy and in-situ environment of this specimen were documented with photographs and the snake was identified unambiguously (Fig. 1). This region has previously been surveyed during 2016 and 2017 and only Masticophis fulginosis (Cope, 1895) was observed during those trips.

Figure 1: Masticophis lateralis individual from San Juanico Bay. A. Ventral body view B. Dorsal body view. C. closeup of ventral head and body. D-F. Locality and habitat where individual was found. Photos from S. Ruane, and B. Simison

Locality Information: Masticophis lateralis Hallowell, E. 1853

New records. (Fig. 1.) Mexico: Baja California Sur: Approximately 15km east of San Juanico Bay (26°19.187ʹ N, 112°23.904ʹ W; WGS 1984; alt: 295m). Observed by Aaron Goodman, Lauren Esposito, Brian Simison, Eric Stiner, Perla Ponce, Ashley Sauer, Sara Ruane, 29 June 2018 at 09:45 hrs.

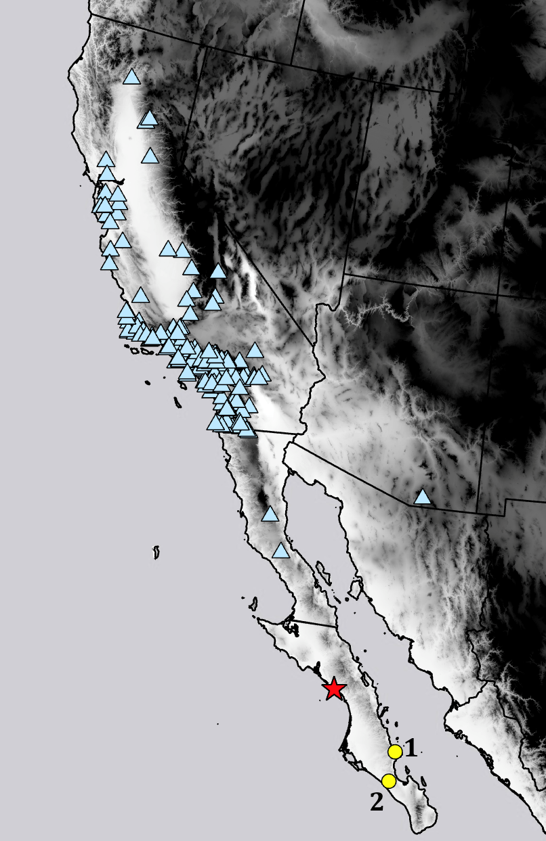

In order to determine if the specimen represented a new locality and subsequent range expansion of the species, we acquired locality records from collected specimens from the past 200 years using theiIDigBio Portal (iDigBio 2018, http://www.idigbio.org/portal), and downloaded the data as latitude and longitude points. We generated a species distribution map using ArcView GIS Version 10.4 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, CA), including the new locality record (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Geographic Distribution of Masticophis lateralis. Blue triangles represent previously collected specimens collected from 1818–2017 (http://www.idigbio.org/portal 2018). Red star indicates our specimen from San Juanico Bay, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Yellow circles represent two specimens previously collected in southeast Baja California Sur (http://www.idigbio.org/portal 2018): 1. Hollingsworth et al. 2003. Fc - Uabc 1116, La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico. 2. Hollingsworth et al. 2004. Fc - Uabc 1260, La Paz, Baja California, Sur, Mexico.

We concluded from our distributional map that this new locality and habitat has not been documented in the species previously, and our finding fills the gap of this species from the Sarcocaulescent shrubland of Cabo San Lucas to the Magdalena plains of northwest Baja California Sur.

Although this species is not endangered, this finding highlights the importance and versatility of online databases to ascertain ranges of species using both historic and recent specimens. Furthermore, this paper serves as a benchmark for future studies whereby distributions of more endemic species within Baja California can be mapped, allowing conservationists to integrate ecoregion, plant community, and species assemblages into decision making, and to prioritize their efforts with greater precision and confidence.

Future research includes the integration of locality records of Masticophis lateralis or other more endemic species of herpetofauna and long-term climactic data to predict future phenological patterns of species. iDigBio hosts a plethora of workshops and crash courses on ecological niche modeling which will be of vital importance for future protection of species in a rapidly changing climate.

We want to thank the Islands and Seas Field Course for the opportunity to explore and learn within Baja California Sur, as well as their expertise in identification of the M. lateralis individual and knowledge of the ecoregion.