American Horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus)

Photo courtesy of: Florida Fish and Wildlife, Photo by: Karen Parker

Although their common name suggests they are crustaceans, horseshoe crabs aren’t really crabs at all. In fact, their closest living relatives are spiders and scorpions. Today’s horseshoe crabs have many similarities to extinct trilobites and look virtually the same as horseshoe crabs that crawled around the ocean floor 480 million years ago! For these reasons, horseshoe crabs are often referred to as “living fossils.”

Of the four species of extant horseshoe crabs, three are found in Southeast Asia and one on the Atlantic coast of North America. The American horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus, is found from Maine to Louisiana, with an additional population on the Yucatán Peninsula. Throughout most of the year, adult horseshoe crabs inhabit the deeper waters of the continental shelf. During the full and new moons of the spring and summer months, however, adults make their way to the sandy beaches and mudflats of estuaries to spawn. As a female approaches the shore, an adult male attaches to her using special pincers. Near the peak of high tide, the female, with male in tow, burrows 10-15 cm into the sand at the water’s edge and lays thousands of tiny, pale-green eggs. As she lays her eggs, the male externally fertilizes them with free-swimming sperm. During a single spawning season, females will visit the beach several times, laying many thousands of eggs each visit. Large females can lay up to 90,000 eggs in a single season! In some areas, thousands of horseshoe crabs come ashore at one time to lay their eggs. The millions of eggs left by these huge spawning aggregations provide food for many species of migratory shorebirds.

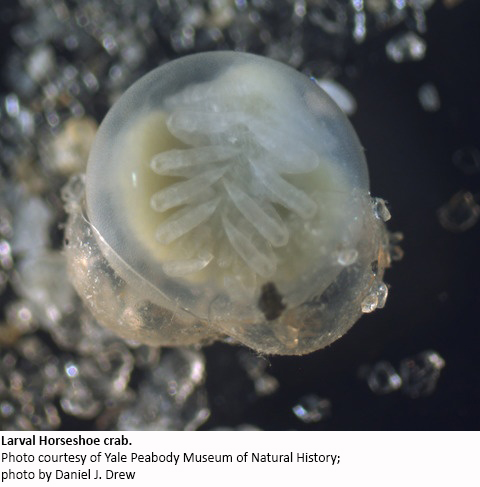

Horseshoe crab eggs develop in the moist sand of their nests for about four weeks. When their nest is again flooded during the high tide of a full or new moon, they hatch from their eggs and emerge from the sand as larvae just 2-3 mm wide. Horseshoe crab larvae and juveniles remain in their natal estuaries for several years. Like all arthropods, as horseshoe crabs grow, they periodically molt, or shed, their exoskeleton. Horseshoe crabs reach sexual maturity when they are about 10 years old, at which time they stop molting and remain offshore until returning to the beach to spawn. They can live to be over 20 years old.

Horseshoe crab eggs develop in the moist sand of their nests for about four weeks. When their nest is again flooded during the high tide of a full or new moon, they hatch from their eggs and emerge from the sand as larvae just 2-3 mm wide. Horseshoe crab larvae and juveniles remain in their natal estuaries for several years. Like all arthropods, as horseshoe crabs grow, they periodically molt, or shed, their exoskeleton. Horseshoe crabs reach sexual maturity when they are about 10 years old, at which time they stop molting and remain offshore until returning to the beach to spawn. They can live to be over 20 years old.

Horseshoe crabs are like nothing else on Earth! Among their many unique traits, their blood contains amoebocyte cells, which are similar to the white blood cells of humans. When these amoebocyte cells come into contact with bacterial toxins, they release chemicals that envelop the bacteria in a gel that prevents the bacteria from proliferating. The special ability of these amoebocytes to detect even the slightest amounts of bacterial toxins is used to test for contaminated medical products. Every batch of injectable drugs, surgical implants, or even tools such as scalpels and needles, must pass this Limulus amoebocyte lysate test.

Every year, about 500,000 horseshoe crabs are collected from the bays and estuaries of the Mid-Atlantic States to be harvested for their blood. Up to 30% of an individual horseshoe crab’s blood is drained at a time, after which the animal is returned to the sea. Estimates of mortality caused by this loss of blood vary, but even if the animal is not directly killed from being bled, their activity level and reproductive potential are hindered until they fully recover. We owe a great debt of gratitude to these ancient and beautiful creatures and should do our best to ensure that they continue to grace the Earth’s stage for another half a billion years.

Learn More

- Find American Horseshoe crab specimen records in the iDigBio Portal

- Learn more about them from Animal Diversity Web.

Article Contributed by: Patrick Norby, a Masters Student in the Invertebrate Collection at the Florida Museum.