Contributed by: Teresa Iturriaga, Rhianna Baldree, Alex Kuhn, Andrew N. Miller

University of Illinois, Illinois Natural History Survey, 1816 South Oak Street, Champaign, IL 61820-6970

We forget because remembering everything is impossible.

We also forget because remembering can be painful and raise too many questions that have no clear answers.

Such is the case regarding many ghost towns. They remind us of the transience of everything.

The MyCoPortal, in connection with the Microfungi Collections Consortium (MiCC), holds records that help us to remember and even reconstruct past times, past places, past geographical areas, past mycobiotas, and past floras. The case of Nuttallburg, West Virginia is an interesting example of the intersection of ghost towns, fungi, and the MyCoPortal.

Figure 1. Nuttallburg panorama in 1926 (National Park Service).

Nuttallburg, a bustling mining community by the turn of the 19th century, takes its name after John Nuttall, an Englishmen (1817-1897) who started working in mines at the age of 11 and who migrated to America when he was 32 years old. Nuttallburg (Fig. 1) is located in Fayette County in south-central West Virginia and was active from 1870 to 1958; today it is a ghost town.

With help from in-laws, Nuttall bought 3.5 square miles of land in the heavily wooded New River Gorge area, which contained rich coal seams. He opened two mines, the first in 1870 and the second one in 1874, operated by the Nuttallburg Smokeless Fuel Company. The coal was transported by the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, which started running through the gorge in 1873 and went westward from Richmond, Virginia. Masonry bridge supports still stand by the railroad tracks; the 340-foot-long bridge, built in 1889, stretched across the New River to the town of South Nuttall. Nuttall built 17 two-family and 80 single-family residences. He also built 80 coking ovens for making steel, which he shipped westward with the coal.

By 1880, the Nuttallburg mine operation was the number one coal producer in Fayette County, and, in 1890, Nuttallburg had 342 residents in 110 company-owned houses stretching a half-mile along the New River and up the sides of the gorge.

In 1900, the town had a doctor, a blacksmith and a company store, plus clubs and athletic teams. Shorts Creek, the town’s drinking water supply, divided Nuttallburg into a black community on its east side and a white community on its west side. Each had its own school, church and worker clubhouse.

Figure 2. Lawrence Nuttall in 1900 (Urban Landscapes, The Field Museum of Chicago).

Lawrence W. Nuttall (Fig. 2) was born near Philipsburg, Pennsylvania on September 17, 1857 to John and Elizabeth Nuttall. He attended the Perryville (Pennsylvania) Academy until 1878, when he moved to Nuttallburg to join his father. With the help of his three brothers-in-law, Lawrence managed and operated the Nuttallburg mines, even staying in New River Gorge with his brother-in-law, Jackson Taylor, after the others moved back to Pennsylvania.

[My father] went out every evening to gather plants and spent all of his spare moments in identifying his finds, among which were a couple of [species] that he could not identify. . . . they were a new discovery. . . . (John Nuttall II)

Though Lawrence made his living managing his father’s mines, he was undoubtedly born a nature lover and observer, interested in plants and in the role of fungi in nature, and his spare time was devoted completely to their study. He collected his first two plant specimens in 1866, at only nine years old. In just seven years, he had collected about 1000 species of flowering plants and hundreds of species of fungi, many of which were named after him. At least 108 of the fungal species were new to science. He collected on both living and decomposing substrates: decaying wood, bark of dead trees, underside of logs, dead limbs and stems, decaying cones, and dead and living plant parts.

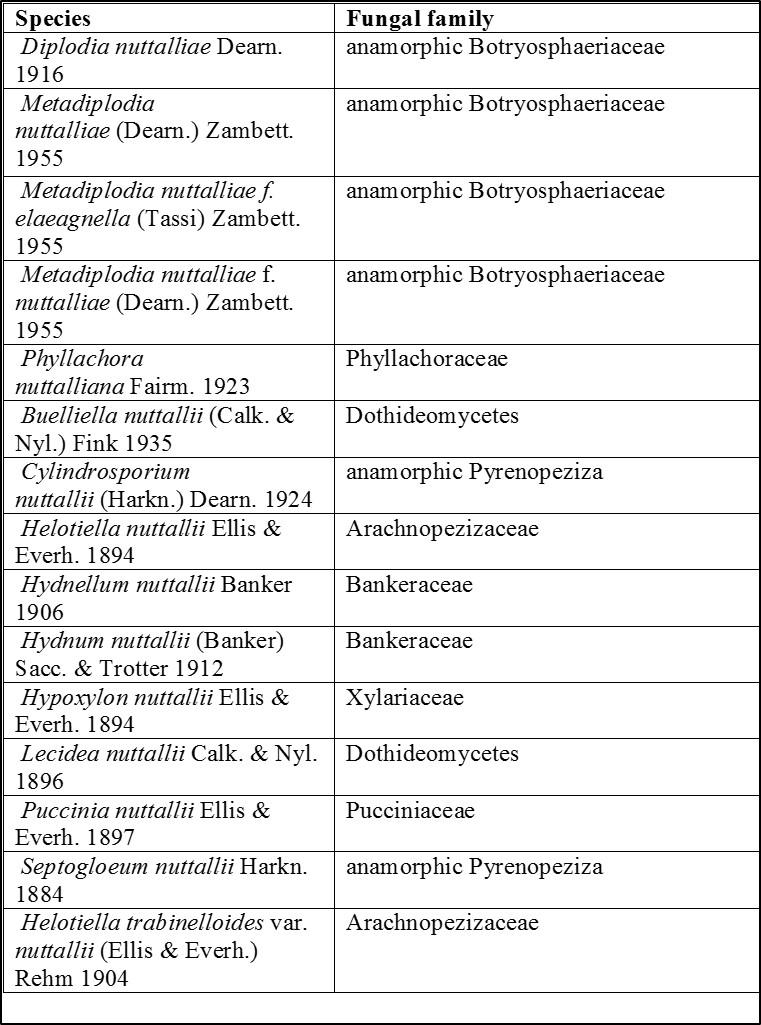

Table 1. Example of some of the fungi collected by L.W. Nuttall with herbaria name and acronyms where these are housed (Data from MyCoPortal, accessed September 2016).

With an ongoing effort to digitize all fungal collections held in herbaria throughout the United States, the number of known specimens collected and distributed by L.W. Nuttall is expected to rise. As of today, MyCoPortal holds over 6000 records of specimens collected by Nuttall, nearly 2000 of which were collected in his home town of Nuttallburg, and are currently housed in different herbaria across the U.S. (Table 1, Checklists 1 and 2). All of these records can be viewed together through checklists created in the MyCoPortal, a tool that has incredible potential for aiding in future research (Checklists 1 and 2).

Nuttall became a highly regarded botanist. Between December 1890 and August 1899, he collected intensively in Nuttallburg. Approximately 300 fungal specimens, mostly collected in 1893, were studied and published by Ellis and Everhart, some as exsiccati, and some in their paper of 1894. Almost seventy were published by them (Ellis and Everhart 1894) as new species with at least three named after him. In addition, more than 10 species of fungi (Table 2), and the same number of plants species have been dedicated to him. Fraser’s Sedge (Cymophyllus fraseri) was apparently discovered by Matthias Kin around 1801, but the plant was lost to scientists until rediscovered by Lawrence Nuttall in the 1890s along New River Gorge.

Table 2. Species of Fungi dedicated to L.W. Nuttall (Data from Index Fungorum, Species Fungorum, accessed September 2016).

Many of Nuttall’s specimens were sent to various authorities for identification, one of whom was botanist C.F. Millspaugh of West Virginia University. After collaborating for several years, they jointly published Flora of West Virginia (Millspaugh and Nuttall, 1896). In succeeding years, Nuttall continued collecting in West Virginia and other areas of the nation, contributing to publications including Flora of the Southeastern States, North American Uredinales, Flora of West Virginia (Millspaugh and Nuttall 1896) and Flora of Santa Catalina Island (Millspaugh and Nuttall 1923). His knowledge about plants and fungi can be appreciated from his publications and by the information he recorded of the hosts upon which the fungi were collected (Checklists 1 and 2).

On November 11, 1884 Lawrence married Katherine DuBree of Pittsburgh, and they had one surviving son, John Nuttall II, named after his grandfather. In 1909 Lawrence made generous contributions to the Presbyterian Church of West Virginia. In 1919 Charles Frederick Millspaugh, the curator of botany at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, wrote to Nuttall asking if he would be interested in investigating the flora of Santa Catalina Island. Nuttall accepted and began collecting there from April to October 1920 and continued intermittently until February 1921. These specimens (#1-1250) are deposited at the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago. The Nuttalls moved to San Diego in 1927, where Lawrence died on October 16, 1933.

The ultimate fate of Nuttallburg itself is rather sad.

The Nuttall family owned thousands of acres of land, operated profitable coal mines, and provided livelihood for hundreds of mine workers and their families. Though John Nuttall died in 1897, Nuttallburg continued to thrive under the direction of his heirs for 61 more years, who controlled the mines until 1920. That year they sold the mines to Henry Ford, who ran the operation under the name Fordson Coal Company.

Several companies such as Ford Motor Company, the Roberts and Schaefer Company in Chicago, and the Fairmont Mining Machinery Company of Fairmont, West Virginia produced from 10,000–240,000 tons of coal in Nuttallburg per year until 1928, when Ford sold his interests in the Nuttallburg mines to the Maryland New River Coal Company, which in turn sold it to the Garnet Coal Company in 1954, the last operators of the Nuttallburg mine. The town was dying. The post office, which opened in 1893, closed in 1955; in 1962 the C&O Railway retired the Nuttallburg depot.

In 1998, the Nuttall family transferred ownership of Nuttallburg to the National Park Service for inclusion in the New River Gorge National River. The recently stabilized mining structures and the town itself, now a mere collection of empty buildings concealed beneath a growing forest, are all that remains of the once-lively mining community. In 2005, the town and its mining structures were inventoried and documented. An interesting forest can be seen in the documents. Today Nuttallburg is a nationally significant protected historic site. It can be visited for a look at traditional coal mining in West Virginia and is one of the most complete coal-related industrial sites in the United States.

A foray or collecting trip to compare the mycobiota that was found in the late 1800’s with what may be seen now, some 120 years later, would undoubtedly yield interesting results.

Checklist 1. Complete list of L.W. Nuttall’s collections (Data from MyCoPortal, accessed September 2016). http://mycoportal.org/portal/checklists/checklist.php?cl=111&emode=0

Checklist 2. Collections from Nuttallburg made by L.W. Nuttall (Data from MyCoPortal, accessed September 2016). http://mycoportal.org/portal/checklists/checklist.php?cl=112&emode=0

References

Boone W 1974. History of Botany in West Virginia. Parsons: McClain.

Core E 1952. Lawrence William Nuttall. Castanea 17(4): 157-164.

Ellis JB and BM Everhart. 1894. New Species of fungi from various localities. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 46: 322-386.

Grafton E 2016. C. F. Millspaugh. e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 07 December 2015. Web. 19 September 2016. http://www.wvencyclopedia.org/authors/90

Kirk PM 2016. Index Fungorum <http://www.indexfungorum.org>

Kirk PM 2016. Species Fungorum <http://www.speciesfungorum.org>

Leo KC 2015. Lawrence William Nuttall. e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 08 December. Web. 19 September 2016.

Millspaugh CF and Nuttall LW 1896. Flora of West Virginia. Fieldiana 9. Botanical series. vol. 1(2), Chicago.

Millspaugh CF and Nuttall LW 1923. Flora of Santa Catalina Island. Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago. Pp. 413.

National Park Service

https://www.nps.gov/neri/learn/historyculture/john-nuttall.htm