A distinct new era for plant specimen use

Contributed by Mason Heberling, Assistant Curator of Botany, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Existing for centuries, plant specimens stored in herbaria have long been the cornerstone of plant biology. Collected by many thousands of botanists, an estimated more than 385 MILLION specimens currently reside in over THREE THOUSAND herbaria distributed across the world. But WHY – Why collect? Why keep? Why curate? Why digitize?

In our recent review paper, Alan Prather (Michigan State University), Steve Tonsor (Carnegie Museum of Natural History) and I analyzed over 13,000 scientific articles published over the last 95 years. We asked: 1) Are herbarium specimens still relevant in modern research?; 2) What are the major uses of herbarium specimens?; and 3) How has specimen use changed through time?

The study was initially motivated by my lack of experience with natural history collections. Although my PhD was in plant ecology, I must admit I had no direct experience with collections until later. I (wrongly) thought collections were a place for taxonomists, not for me. When the National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellowships in Biology included a Research Using Collections track in the solicitation, I was intrigued, but quickly wrote off the idea as a stretch for my research. Then, I recalled a few influential studies that used specimens to track changes in introduced species through time and became excited to extend this approach to my plant invasion research.

During my postdoc, I regularly overheard tours of the collection. “Novel” uses of specimens were commonly given as key examples of specimen use alongside the “traditional” uses. Many recent studies used the collection to look at the effects of human-caused environmental changes like climate change, pollution, invasive species, and urbanization. My perception of the uses for specimens were certainly not the only uses. We wanted to assess whether our speculated trends in herbarium use was supported by the published uses of specimens.

Herbarium specimens serve critical roles in taxonomy and systematics (including species discovery, species description, and understanding the tree of life), floristics (what species live where), species identification (reference material), science education, and scientific vouchers (essential to the verifiability and repeatability of our science). These “anticipated” uses remain a critical and necessary function of herbaria. But specimens are increasingly used in unanticipated ways. How do these “new” uses of specimens compare to historical uses? A broader understanding of the trends in herbarium specimen use will promote continued development for the next waves of specimen use.

To examine the scope and trends in herbarium use, we started with relatively routine literature database searches for “herbarium” and related key words to find as many published studies we could that mention herbarium specimens or specimen-derived data in the title, abstract, and/or keywords. With nearly 14,000 papers, a careful read of every paper was not feasible. Beyond the time limitation, manually categorizing that many papers into pre-defined topic areas would be challenging to do in a standardized, unbiased way. We used an approach called topic modeling (also called automated content analysis) to synthesize trends in the herbarium-based literature. In short, it is a computer-assisted method of text analysis that defines topics based on word co-occurrence within and between papers and their use across the entire set of papers of interest (in this case, studies mentioning herbarium specimens). Each study abstract is then classified according to these identified topics. Topic models are more commonly used in the social sciences and humanities (a common research tool in the field of “digital humanities”), but topic models are increasingly applied in ecology and evolutionary biology.

So, are herbaria still relevant? Most collections advocates probably already know the answer, but it is helpful to have the numbers to back it up! We found that herbarium specimens remain as active resources for modern research, with publications using herbarium specimens dramatically increasing in recent decades. And this increase is comparable to that of all plant science publications. Indeed, herbarium specimens are not an outdated thing of the past but very much relevant and necessary for modern research.

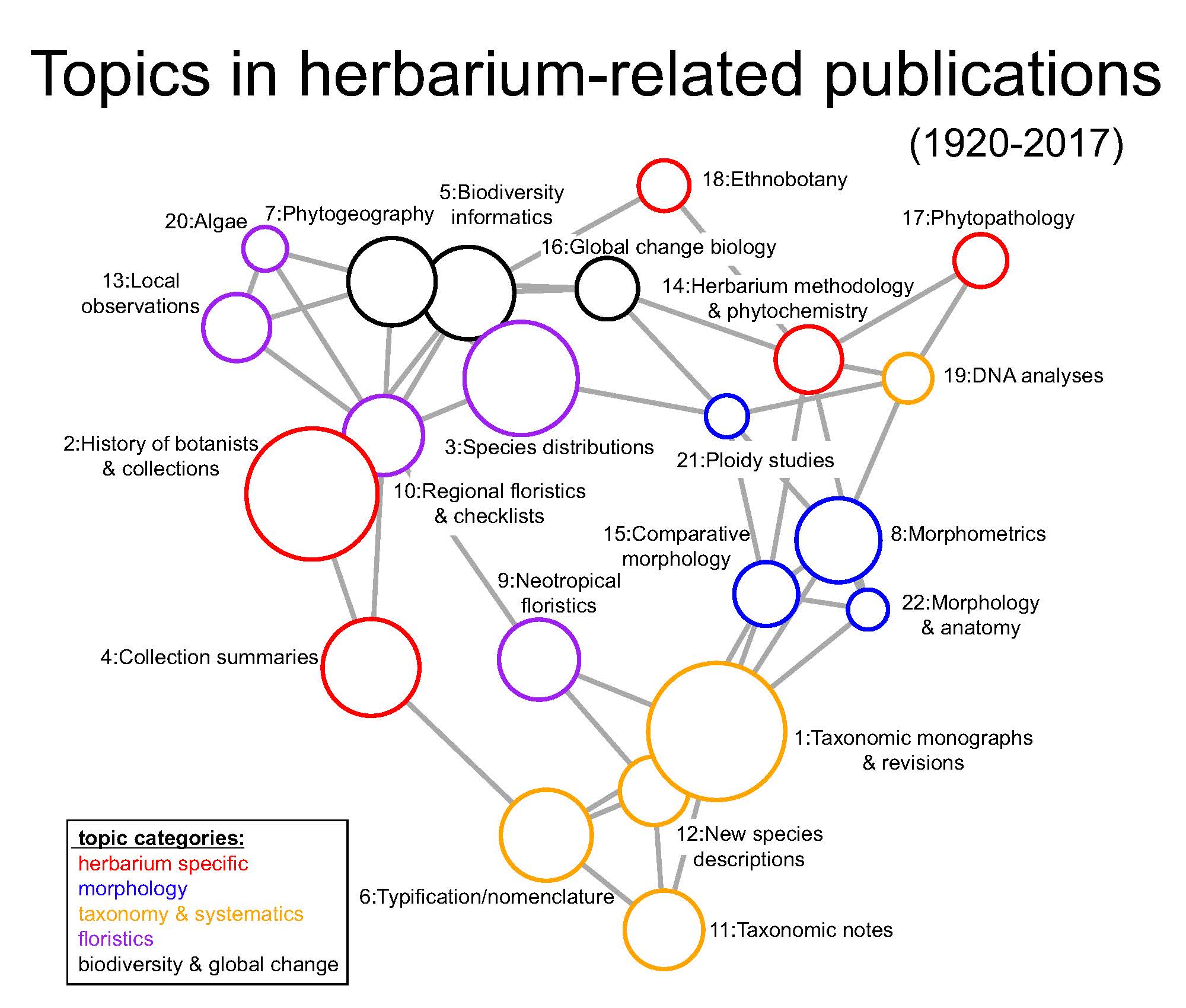

The topic models provided a quantitative approach to understanding trends in herbarium-related studies, identifying 22 topics in these herbarium-based studies. Each study could be assigned to more than one topic. Topics ranged from those related to taxonomy and systematics (such as taxonomic monographs, the most frequent topic), morphology (such as morphometrics), herbarium specific (such as botanical history or collection summaries), floristics (such as regional checklists), and biodiversity/global change biology (such as studies on biological responses to past and future environments). While some topics were more common than others, no single topic overwhelmingly dominated the literature. And importantly, no major topic disappeared from the literature!

Figure 1: Illustration of associations between topics identified in the herbarium-related literature through a topic correlation network. Topics near each other are more likely to appear together within study abstracts. The relative sizes of the circles are proportional to their overall prevalence in the literature. Topics grouped into color-coded categories as a visual aid.

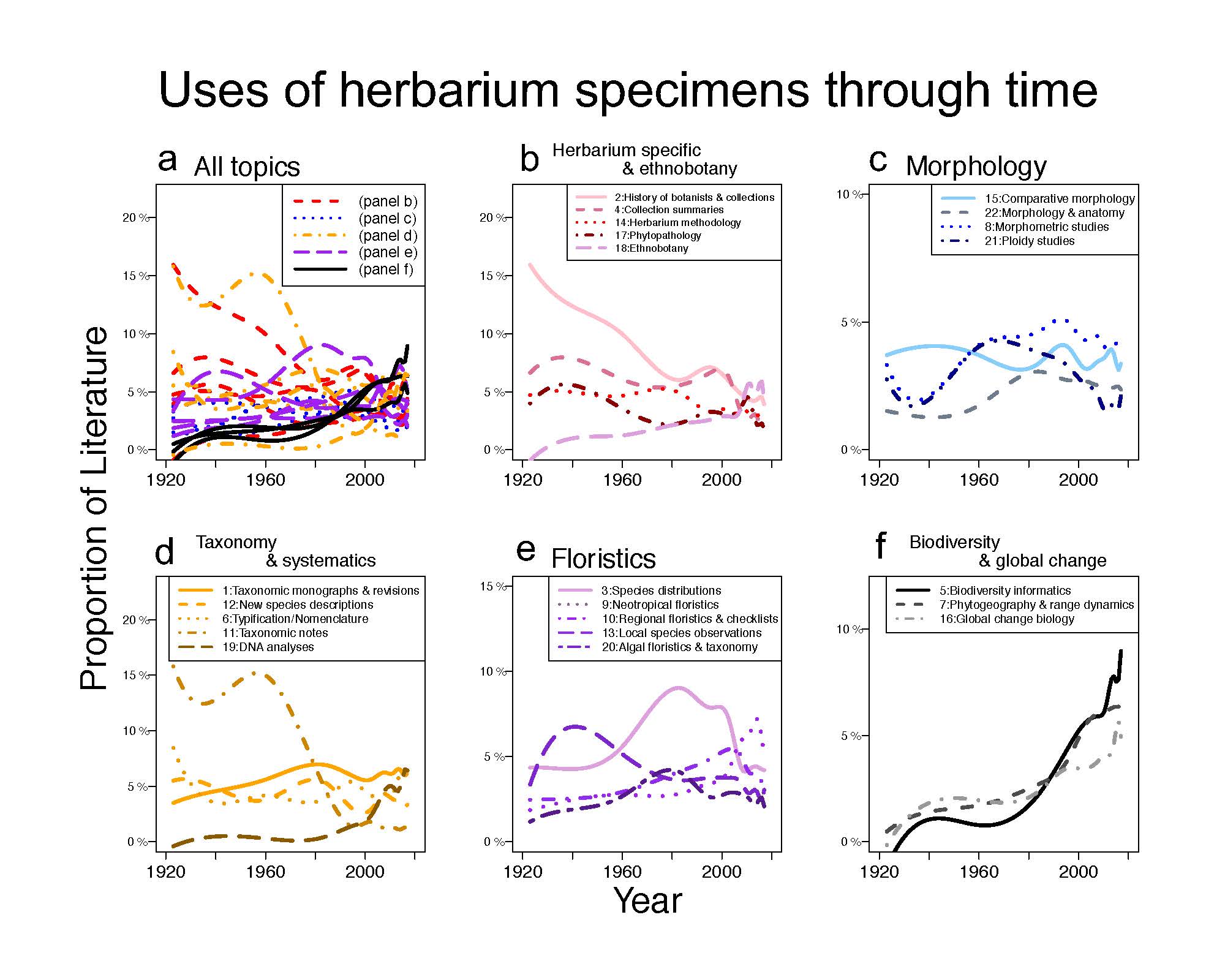

The biggest take home: herbarium use has diversified over the past century. Published herbarium use was once dominated by only a few taxonomically based research topics. Throughout the past century, many new uses for specimens have emerged, including topics of biodiversity informatics, global change biology, and DNA analyses. Despite only emerging in recent decades, studies involving new tools and approaches make up 16% of all analyzed studies published over the past 95 years: biodiversity informatics (including niche models using digitized specimen data) accounted for 5% of studies; global change biology (using specimens to look at plant responses to past and future environments) accounted for 3%; DNA analyses (using specimens for genetic data) accounted for 3%; and phytogeography and range dynamics (including analyzing invasive species spread) accounted for 5% of studies.

Figure 2: Topic prevalence over time in herbarium studies (1920-2017), as estimated from a topic model of 13,702 abstracts. The vertical axis indicates the proportion of literature in a given year associated with a given topic.

An exciting, distinctly new era for herbaria is upon us. Widespread digitization and new perspectives have enhanced longstanding research use and enabled our ability to answer new questions altogether. These conclusions can likely be extended to natural history collections more generally. Specimens are primary sources of biodiversity knowledge and are increasingly used in ways that influence our ability to steward future biodiversity in the Anthropocene. We must continue to collect, curate, and rethink how we do both of those things. We may not know exactly how specimens will be leveraged in the coming decades, but herbaria are well poised for a strong future.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation grant no. DBI 1612079. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.